Keynote: What is a Poem?

- Andrew Jamison

- Oct 21, 2025

- 23 min read

Read Andrew Jamison's keynote poetry lecture, originally delivered at the University of Reading on Monday 20th October 2025.

Subscribe to my blog here and join almost 200 others who get my weekly newsletter every Monday morning.

What is a Poem?

Lecture to Third Year Undergraduates

University of Reading

20th October 2025

1. A piece of writing or an oral composition, often characterized by a metrical structure, in which the expression of feelings, ideas, etc., is typically given intensity or flavour by distinctive diction, rhythm, imagery, etc.; a composition in poetry or verse.

Oxford English Dictionary (definition of ‘Poem’)

‘Poemys [Latin poesis] after myn oppynyon delyten the mynde of man with wanton pleasure.’[1]

John Skelton, c 1487

‘Poetry is not the thing said, but a way of saying it.’ [2]

A. E. Housman

‘My definition of poetry would be this: words that have become deeds.[3]

Robert Frost

‘…simple, sensuous and passionate.’[4]

John Milton

‘Writing poetry is a way of life… not a matter of interpreting the world, but a very process of sensing it.’[5]

Elizabeth Bishop

‘Imaginary gardens with real toads in them.’ [6]

Marianne Moore

‘Poetry should be great & unobtrusive, a thing which enters into one’s soul, and does not startle it or amaze it with itself but with its subject.’[7]

John Keats

‘A poem is that species of composition, which is opposed to works of science, by proposing for its immediate object pleasure, not truth…’[8]

Samuel Taylor Coleridge

‘For all good poetry is a spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings.’[9]

William Wordsworth

‘A poem should be equal to:

Not true.

…

A poem should not mean

But be.’[10]

Archibald MacLeish

‘Poetry is not a turning loose of emotion, but an escape from emotion; it is not the expression of personality, but an escape from personality.’[11]

T. S. Eliot

‘Poetry is the art of uniting pleasure with truth, by calling imagination to the help of reason.’[12]

Samuel Johnson

‘If I read a book and it makes my whole body so cold no fire can warm me, I know that is poetry. If I feel physically as if the top of my head were taken off, I know that is poetry.’[13]

Emily Dickinson

‘Now for the poet, he nothing affirmeth, and therefore never lieth; for, as I take it, to lie is to affirm that to be true which is false…’[14]

Sir Philip Sidney

‘Poetry makes nothing happen.’[15]

W. H. Auden

‘A poem is a large (or small machine) made of words.’[16]

William Carlos Williams

‘A poem is a little machine for remembering itself.’[17]

Don Paterson

‘My opinion is that a poet should express the emotion of all the ages and the thoughts of his own.’[18]

Thomas Hardy

‘There must be three things, I would suggest, before the poetry can happen: soul, song and formal necessity.’[19]

Derek Mahon

What is a Poem?

‘What is a poem?’, despite its brevity, is a big question; it’s maybe the biggest one we could pose. And yet at the same time it might seem like the kind of question asked in a primary school classroom as opposed to a university environment like the one we find ourselves in now. Indeed, it’s the kind of question that could well be answered in a primary school classroom with an answer such as ‘words that rhyme’ – which wouldn’t be wrong in the least. But, maybe we should give the childlike sensibility and way of seeing more credit, for wasn’t it Wordsworth who said ‘the Child is Father of the Man’[20]? And didn’t Picasso once assert ‘when I was the age of these children I could draw like Raphael: it took me many years to learn how to draw like these children’?[21] Entering into the world of poetry with the unabashed, unspoilt, unpretentious curiosity and viewpoint of a child, may not be such a bad starting point, and if it’s good enough for Wordsworth and Picasso, perhaps it should be good enough for us.

Some might think to themselves: ‘We’ve read many poems, and what the theorists have to say about poetry, and we all know what a poem is.’ Some might even be of the persuasion that literary theorists who write about ‘poetics’ are more qualified to define poetry than poets themselves, and maybe there is something in this. Jacques Derrida, renowned theorist of deconstruction, defined it as a ‘benediction before knowledge’[22] which has its attractions, particularly in how it seems to confer on the art sacred, holy connotations, even if it’s not entirely clear what he actually means. The point I’m making here is that maybe definitions of poetry, the business of defining it should perhaps be the preserve of those who don’t write it – I mean, why would poets need a definition for what they do, if they’re just compelled to do it anyway? But, no sooner do we start answering the question than we find ourselves questioning our initial thoughts: ‘No, it’s not just that. I suppose a poem could also be X, Y, or Z.’ Dennis O’Driscoll, in his entertaining Bloodaxe Book of Poetry Quotations quotes Samuel Johnson:

Boswell: Sir, what is poetry?

Johnson: Why, Sir, it is much easier to say what it is not.[23]

I like this little exchange, but I’d question whether it is really easier to say what poetry is not, as it always seems to come back with the opposite argument.

A Question of Devious Simplicity

But, when we look a bit closer, I think questions like this one are devious in their simplicity, and we are more the fool to ignore them or pass them off as beneath our intellect. If anything, it’s the simplicity of the question which attracts me to it the most. As someone who has published a few collections of poetry, and is in their final year (hopefully) of a PhD, under the tutelage of great experts, in all honesty, I still can’t help but feel a bit stumped by this question. I mean, what is a poem? From spending so much time with these little stumps (and sometimes big lumps) of language that hug the margin of the page (or sprawl all over it), it’s easy to lose perspective about what, at heart, defines a poem. So, ‘What is a poem?’ then, far from the primary school classroom, is not only a question still worth asking, but becomes a fiendish, indeed huge philosophical question, not least an existential one for those of us who write it and try to spin what might be called a life from it.

But, stick with me and I think you’ll find that in asking this question it might lead us to thinking about, seeing and reading poetry in new ways.

A Labyrinth of Definitions

So, after all of the quotations that prefaced this talk, from some of the most canonical poets in history, are we any the wiser as to what a poem actually is? Reading these definitions, we have some poets who propose that poetry is all about expression and emotion (Wordsworth, Dickinson), then some who believe that it’s only when we detach ourselves and disconnect our personalities that poetry can happen (Eliot). We have some like Keats who strive for truth, and some like Sir Philip Sidney who believe poetry lies in, well, lies. We have some who believe poetry is all pleasure (Skelton) and some who believe it’s like a machine (Carlos Williams and Paterson). For some it’s a vocation (Bishop) and for others it’s about capturing something fleeting in moments of inspiration (Wordsworth, Coleridge, Keats). For Auden it makes nothing happen, yet for Robert Frost the words of poems themselves are deeds. Archibald MacLeish goes further by suggesting the poem is a living organism. So, I ask you again, dear reader, where does this leave us?

This talk is entitled ‘What is a Poem?’ yet already we are bamboozled, and paradoxically the more definitions we read (and by the way, the ones I’ve chosen barely scratch the surface) the less we seem to be able to cage this strange, flighty little creature, that is (or is it?) the poem. So, the title of my talk today, in many ways is misleading. Indeed, it can at times feel like we stand in a labyrinth of past masters all shaking their books at us, vying for their definition to be the definitive one. So, I’m sorry to say, that if you haven’t already guessed, I’m afraid that I’m not going to be able to give you a single answer. Moreover, as Samuel Johnson puts it: ‘To circumscribe poetry by a definition, will only shew the narrowness of the definer.’[24]

Impossibility of a Definition

I’d go as far as to say, straight off the bat, that the poem is impossible to define, as much as we would like to, and as eloquent and shocking and moving as we can be about it, if this plethora of quotations has taught us anything it’s that poetry is oddly, not undefinable (there are many definitions), but resistant to being captured and explained by one singular sentence, to the point where we start to get suspicious whenever we read any phrase that begins with ‘poetry is…’ because, dear reader, invariably it is always more than that, or at other times its opposite. Even if we were to say: poetry is undefinable, that’s simply not true – we have a wealth of definitions, and in fact, I’d argue that the more definitions we have, the further away from it we start to move. But, isn’t this the fun of poetry? And don’t we get the sense that this is how poetry itself likes it?

But, all is not lost. And I want to propose another way of arriving at, not only a definition of poetry, but something more than that, a way of reading poetry which allows us to define or take every individual poem we read in its own way, and in doing so make unsurprising connections with others. In order to do this, I’m going to suggest one simple adjustment to the title of this talk, and instead of asking ‘What is a poem?’ I’m going to suggest we ask ‘How is a poem?’ And in asking this question, we might hope to arrive at ‘Why is a poem?’ which is surely the most important question we need to consider, particularly in uncovering that poem’s particular network of influences.

How is a Poem?

Now nothing but claptrap

About ‘mere technique’ and ‘true vision’,

As if there were a distinction – [25]

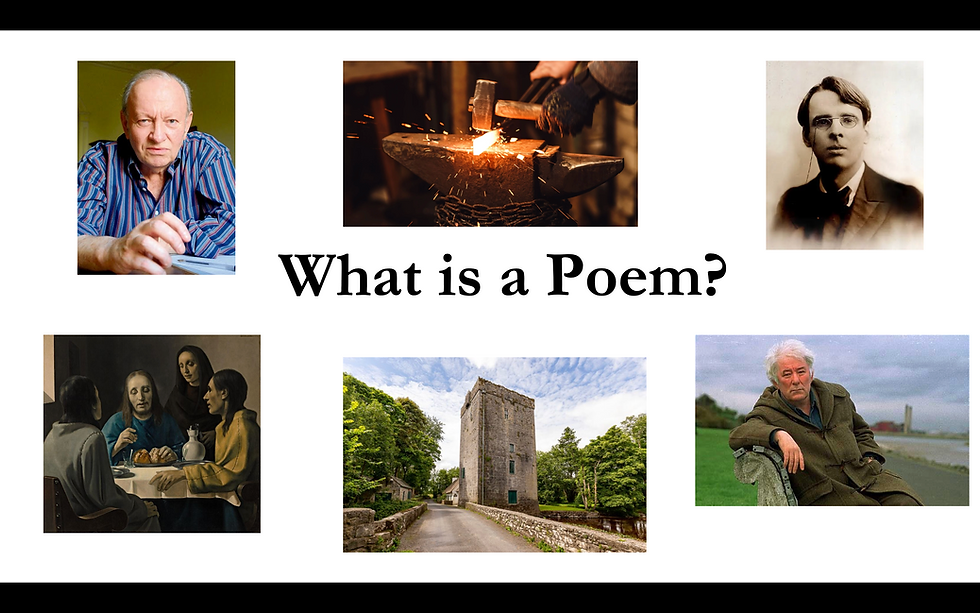

I’m going to start this section with a quote by Derek Mahon, late Northern Irish poet, as I think it captures what I want to say here in a very poetic, and concise manner, and probably more concisely than I will be able to say it. I’m going to suggest that by investigating how a poem is written, its techniques as Mahon refers to here, we understand not just the vision of that poet, but uncover a network of influences their language engages with. In these prefaced lines, Mahon is suggesting that the vision of the poet is not simply glimpsed in its technique, but is the technique. What I am supporting the case for here is close reading – it’s nothing new, but I think from time to time it’s worth reasserting what we think to be the best ways of reading poetry, particularly, in the light of this essay, with a view to restoring and preserving excellent poems from the past. Let me illustrate this by way of example, by looking at two poems which concern themselves with the verb ‘forge’: one by Derek Mahon, already quoted here, ‘The Forger’, and one by Seamus Heaney entitled ‘The Forge’. You might be wondering why I’ve chosen the word ‘forge’; the main reason is that it relates to the ancient etymology of ‘poem’, the ancient Greek word πόημα (from 4th century B.C.), an early variant of ποίημα, meaning thing made or created, work, poetical work.[26] The idea of forging something or making something is intrinsically, linguistically bound up in the etymology of ‘poem’ itself. By reading both poems carefully we can see how both poets, both from Northern Ireland in the same era, use these poems as methods of outlining something of their own writing processes, using images of light and dark, while probing the idea of creation, where it comes from (the tensions between creation and restoration, and indeed the restorative power of poetry), exploring ideas of heritage, as well as questioning their own authenticity and authority as poets.

Forges, Forgers and Forgeries

I, the poet William Yeats,

With old mill board and sea-green slates,

And smithy work from the Gort forge,

Restored this tower for my wife George;

And may these characters remain

When all is ruin once again.[27]

Before we look at these two poems of Mahon and Heaney, though, I want to look at this little poem by W. B. Yeats which he wrote to commemorate the tower that he restored in Ballylee which is still there today. It’s a poem which, once we’ve analysed his methods, helps us lay the ground for a deeper understanding of the tradition of Irish poetry, particularly in the work of Heaney and Mahon. It not only connects the poems of Mahon and Heaney in its use of the word ‘forge’, but also highlights a particular concern of Irish poetry: the tensions between restoring and preserving tradition and history in the face of the modern, rapidly advancing world, particularly in a country which seems, as history would tell us, intent on tearing itself apart. We note here Yeats’ reference to the nearby ‘Gort forge’; in a six-line poem, it’s noteworthy that of all the trades he could have referred to in commemorating the building he refers to the forge, and not just the place but singles out the ‘smithy work’ as crucial in how the building was – and here’s the crucial word – ‘restored’. One of Yeats’ missions as a writer was to restore the stories and folklore of Irish language as part of the Irish Literary Revival. But as we will see in our exegesis of the following poems, this idea of restoration and Irish literature carries on to later generations and was inherited, albeit in their own ways, by Mahon and Heaney. Indeed, the poem’s full title is ‘To be Carved on a Stone at Thoor Ballylee’, which suggests that not only does Yeats want to immortalise the place in verse, but also for the verse to be physically memorialised, indeed he intimates it will be ‘these characters’ of his verse which will ‘remain’ when all is ‘ruin once again.’ Yeats is forewarning of the eventual decay and need for restoration required not just in the physical word, but also the poetic one. Just as he has needed to restore the Irish folk tales as part of the Irish Literary Revival, so too is he predicting a time of ‘ruin’ in the world of literature as much as in the physical texture of the world, hoping ‘these characters’ of his language survive – there is a note of uncertainty, hope and perhaps a little desperation in his use of the modal, permission-seeking ‘may these characters remain…’ We can’t help but feel that ‘characters’ such an ambiguous word in itself, could also refer to the national character of Ireland, which he poured so much of the artistic energies of his life into maintaining and, quite literally, reviving and restoring. His use of ‘stone’ as the material also emphasises his intention for the memorial to last in itself, as much as the tower it is memorialising; after all, he ends the piece by writing ‘may these characters remain/when all is ruin once again’, with ‘characters’ pointing to the characters or features of the property, as much as the characters or letters of his verse. What Yeats shows here, then, in the restoration of the tower, is how he’s more interested in restoring something than creating something from scratch, and in doing so, he’s thereby able to improve upon the original. In essence, for Yeats, to restore seems to be to create, and to create seems to be to restore, and this process itself for Years is restorative, in an emotional sense; we can see this physically in his tower at Ballylee, a thriving tourist destination today where the characters have remained, but also in his work as a whole, particularly in how he was a leading figure of the Celtic Revival.

So, in paying attention to the details of Yeats’ poem here we have tapped into the psyche of Irish poetry, its vision of restoration and anxieties surrounding preservation. But, how – and remember that’s the key word here – has this six-line ditty of Yeats got anything to do with the other two poems I’ve mentioned written over one hundred years later? Let’s begin by taking another minor detour – forgive me, we’ll get to the main event soon.

Another Minor Detour

Commenting on a period of many years of writer’s block, Michael Longley, a contemporary of Heaney and Longley once commented: ‘I wasn’t completely silent, but everything I wrote was stillborn, it was bad. I’m proud of the fact that I didn’t produce forgeries.’[28] While this comment was made more than thirty years after the publication of Heaney’s ‘The Forge’ and Mahon’s ‘The Forger’, I’m struck by the use of the word ‘forgeries’ here, and how for Longley there seems like there could be nothing worse than a poem which could be read as an imitation of something that has come before. In many ways, then, Longley would appear to be at odds with both Heaney and Mahon, who both seem to be suggesting, in these two poems at least, that an essential quality of a poem is that has in some way inherited something of old, or replicated, perhaps in a new light a new form or idea present in the tradition of the art. Perhaps Longley should have been producing forgeries in those barren years, but more so in the way that Heaney and Mahon have come to think of a forgery as more of a Yeatsian renovation, restoration job, as we’ll see in the following analyses of their methods.

Heaney and Mahon

Let’s begin with Mahon’s poem ‘The Forger’, the noun ‘forger’ is loaded with meaning as it could simultaneously mean one who forges (creates) but also refer more specifically to one who produces counterfeit replicas of original artworks. Mahon is referring to both here and as we read the poem, we start to see that while Mahon is assuming the voice of a character (the infamous forger of Vermeer’s work was Han van Meegeren, but that’s the beside the point), he’s also suggesting that he himself, the poet, is a forger to some extent, borrowing or stealing from influences. As T. S. Eliot wrote:

One of the surest of tests is the way in which a poet borrows. Immature poets imitate; mature poets steal; bad poets deface what they take, and good poets make it into something better, or at least something different.’[29]

This is the part that’s often quoted, but an even more interesting moment occurs afterwards when he writes:

‘The good poet welds his theft into a whole of feeling which is unique, utterly different from that from which it was torn; the bad poet throws it into something which has no cohesion.’[30]

Note T. S. Eliot’s use of the verb ‘weld’ here, the idea of using high heat to join metal together – it’s a physical, technological image of labour, and chimes with Seamus Heaney’s in ‘The Forge’, where the noun is chiefly used as a place name, i.e. a dark place of fire and heat, where the blacksmith creates, adapts, shapes or mends horseshoes by hand. As opposed to the idea of forgery, as intimated with Mahon, Heaney’s poem, on the surface, is concerned with ideas of authenticity and originality, after all the blacksmith wants to ‘beat real iron out’. He seems to use the blacksmith as a metaphor for his own craft and artistic process where the ‘immovable’ ‘altar’ of the anvil is the form of the poem itself. In the case of this poem the ‘altar’ is a sonnet, one of the oldest forms of poetry there is, which offers resistance to his ideas and expression, but in turn gives them shape. We note, for example, that the volta of the poem occurs after the line ‘set there immovable: an altar’ and then moves into the sestet which begins ‘where he expends himself and shape and music.’ The ‘shape and music’ of the blacksmith mirrors neatly Heaney’s own movements as a poet in the poem, specifically here the movement between the octet and the sestet of the sonnet. Heaney himself referred to the poem as using ‘the dark active centre of the blacksmith’s shed as an emblem for the instinctive, blurred stirring and shaping of some kinds of art.’[31] Initially, there is no hint here at Heaney suggesting that the idea of the forge is to recreate, as in Mahon’s poem, but create for the first time. But when we look more closely, we can see that it’s more complex than that, and Heaney may indeed be suggesting the former.

Replication and Recreation

Both poems are interested in the idea of taking a template and recreating it. Mahon writes clearly of this in the opening to The Forger:

When I sold my fake Vermeers to Goering

Nobody knew, nobody guessed

The agony, the fanaticism…

In Heaney’s poem the farrier is making a ‘new shoe’ but only in the image of a fixed frame well known to him. In Mahon’s poem, the forger is recreating, replicating the paintings of Vermeer even if ‘at one remove/ the thing I meant was love.’ Both Heaney and Mahon use the verb ‘forge’, to create, not as a word that means making something totally original but making something that is rooted in a tradition, taking a model, aspiring to it and playing with it; in essence, we can say that both are occupied, to a large extent, with the idea of recreation. We can see this in Heaney’s very use of the sonnet form, for example. In the way the blacksmith is working to a template, so is Heaney in using the poetic form of the 14-line sonnet, replete with the volta and iambic pentameter and rhyme scheme. These ideas of tradition and influence would have been weighing heavily on Heaney as he published this poem in his 1969 second collection, A Door into the Dark. Mahon’s poem was published in his first collection, Night-Crossing in 1968, but has since been removed from his New Collected Poems (Gallery Press, 2011). Perhaps he felt like it showed his influences of the likes of MacNeice too heavily, as MacNeice was fond of referring to paintings, was mentored by Anthony Blunt, had a relationship with artist Nancy Sharp, and wrote such poems as ‘Poussin’, and lines such as in ‘Nature Morte’ as ‘even a still life is alive.’[32] In a poem about influences, perhaps Mahon felt his own were too visibly on display.

Light and Dark

So, both poems, then, come from the poets’ early collections and grapple with ideas of influence and being in the shadow (quite literally) of past masters. In Mahon’s poem it ends with how the forger is misunderstood and how they have ‘suffered/ obscurity and derision,/ and sheltered in my heart of hearts/ a light to transform the world.’ A metaphor for the figure of the poet, if there were ever one. But, before this, Mahon has the speaker walking the ‘dark streets of Holland’ so we can see this interplay of light and dark. We may think the ending is a hopeful one but when we look more closely we can see that the light was ‘sheltered’ in the forger’s heart and therefore never really released, so in essence the forger’s mission is an unfulfilled one, shot through with the ‘agony of regrets’, even if he meant well and sold his ‘soul for potage.’ The forger’s recreations, unlike T. S. Eliot’s definition of a poet who borrows, did not improve the original. Throughout the poem Mahon slips in and out of rhyme with an irregular pattern. Even when words do rhyme some of them are really quite partial such as ‘frauds’ and ‘methods.’ This irregular rhyme scheme I’d argue was a conscious choice by Mahon to imitate the slight weaknesses, infidelities or shortcomings in the work of the forger, a person who makes a living by reproducing the work of others. Mahon tries to lend a sense of authenticity to the character, suggesting they were motivated by not only admiration for the original but by trying to surpass them as he writes: ‘the fanaticism/ of working beyond criticism/ and better than the best.’ As this was Mahon’s first collection of poetry, we get the sense in this poem that he, himself, is setting out with a sense of anxiety about his influences and trying to reconcile the quarrel in himself, to use a phrase by Yeats, one of his forebears, of between balancing the traditional skills and ‘techniques’ of poetry in order to create not necessarily something brand new, but a replica, a version of poetry that might be better than the best, even if he might feel like a fraud or impostor, ripping off his influences despite his best intentions. This sense of insecurity and imposter syndrome was something Mahon grappled with all his life, as he writes of how his father used to repeatedly ask him ‘When are you going to give up the poetry nonsense?’[33] Hardly a ringing endorsement or nod of approval. We get the sense from reading this poem, and examining how it’s been written, that Mahon believed that poetry was something that was endlessly recreated from the poetry that has gone before, as opposed to simply produced in a vacuum, and as a result the poet feels a sense of not just indebtedness to poets like Yeats but almost shame in the act of writing. He writes ‘A good poem is a paradigm of good politics - of people talking to each other, with honest subtlety, at a profound level. It is a light to lighten the darkness; and we have darkness enough, God knows, for a long time.’[34] It is the phrase of ‘people talking to each other’ here which I think is central – for both these Irish poets, being in dialogue with the past seems to be at the core of their creative energies.

Light in Door into the Dark

We see this literally in the work of Heaney, with the first line of the poem ‘All I know is a door into the dark’, the line from which he chose the title for the book, ‘A Door into the Dark.’ There is a great tension in that first line between knowledge and uncertainty – all the poet knows is, not just darkness, but a door into the darkness. There is a sense that Heaney is suggesting that all he knows is the means through which to access the darkness, but not the darkness itself, whatever that darkness might represent: knowledge, wisdom, wonder, love, sex, death. It’s fitting that the first line itself functions as this door. The first line of the poem mimics the opening of the very door Heaney is referring to: the door of the imagination. By reading the first line of his poem we are stepping with him into the dark (note his use of dark, not darkness here – dark is much starker and more defined than its partial relative darkness – it also sets up a rhyme with ‘sparks’ in line 4, which brings out this tension of light and dark). At any rate, the poem begins with a kind of anti-assertion: the poet is asserting that he is unable to assert. So, to circle back to my original idea about how we might understand why a poem has been written by examining its methods, we can start to see here that Heaney’s use of the sonnet, his tensions between light and dark, his metaphor of the blacksmith for his own work, his use of rhyme and rhythm, show a writer at the start of his career, in search of originality and authenticity but at the same time feeling a tension with tradition and influence, and the way things are done, cowed almost by the ‘altar’ that is the poem (a Derridean benediction if there was ever one) and poetic form, uncertain in the dark as outside the modern world and its traffic is ‘flashing in rows’. It shows a poet who is at once balancing the ancient, bygone traditions of poetry, such as the sonnet, and wondering how the values and virtues of poetry can be shaped for the modern world. Finally, there is also something of the poet, coming from a rural, hands-on, farming community as Heaney did, trying to reconcile his endeavour and work as a poet, with the manual labour and work of his relatives, and perhaps it is this influence, above and beyond any literary one, which looms largest for him here as it does throughout his oeuvre. We get the impression that, just like Mahon’s forger, Heaney feels a sense of inadequacy or inauthenticity when comparing himself to the farrier who beats ‘real iron out’ inside the forge, as opposed to Heaney who remains outside looking in, at the threshold of the ‘door into dark’ which is ‘All I know.’ In addition, The Forge, as a poem, we might say, becomes a forgery, in itself, of an image from the poet’s country upbringing, a kind of echo which would be apt as Heaney writes of how the last line in Death of A Naturalist echoes with the opening line of The Forge, and how ‘the two directions of my poetry were ‘to see myself, to set the darkness echoing.’’

Why is a Poem?

So, this has been my example of how when we ask a slightly different question such as ‘how is a poem?’ we arrive at not only what the poem is, but why it exists. It seems clear to me that in observing how Heaney chose to write in the sonnet form and all of the other techniques I’ve just mentioned, we come to understand more about what he’s writing about and why he wrote it i.e. to explore his own insecurities about his pursuit as a poet, and the function and purpose of ancient verse forms in the modern world, as seen in the metaphor of the farrier’s shaping the horseshoe juxtaposed against a backdrop of traffic ‘flashing in rows’. For Mahon, it’s a similar story – a poet who adopts the character of a forger to capture something of the poet’s own insecurity in creating a truly original artwork that is entirely authentic and his alone.

Finally, why have they written their poems? Both poets then are concerned with the genesis of artistic works, and the complications involved in the act of creation, in writing a poem. For these two poets, a poem is as much about creating an original as it is preserving the tradition from which their writing is borne out of, as much as it is about restoring the tradition and the status of the art all over again so as it may, to circle back to Yeats, ‘remain/ when all is ruin once again.’ The poems ultimately highlight the complex tension between influence and ambition, and an abiding hope of the restorative power of poetry, and how it might foster in our ‘heart of hearts/ a light to transform the world’ by expending ourselves in ‘shape and music.’

So, what is a poem?

After all of this, let’s return to our initial question: what is a poem? And the answer to that, we can now say with high degree of certainty is: we’re not sure. It depends on the poem, who wrote it, how we read it and where we can trace its influences. But, don’t quote me on that.

References

[1] Diodorus Siculus, The bibliotheca historica, (translated by John Skelton) (ed. Frederick Millet Salter and Harold Llewelyn Ravenscroft Edwards) · EETS edition, 1956–1957 (2 vols.) (EETS 233, 239).

[2] A. E. Housman, ‘The Name and Nature of Poetry’, in A. E. Housman: Selected Prose, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1961) 187

[3] Robert Frost, ‘Some Definitions’, in Collected Poems, Prose and Plays, (New York: Library of America, 1995) 701

[4] John Milton, Milton’s Tractate on Education, (London: Cambridge University Press, 1905) 16

[5] Elizabeth Bishop, in JM. Baskin’s ‘Elizabeth Bishop’s Poetry of Perception. In: Modernism Beyond the Avant-Garde: Embodying Experience. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018) 31

[6] Marianne Moore, ‘Poetry’ in The Faber Book of 20th Century Women’s Poetry, (London: Faber and Faber, 1987) 50

[7] John Keats, To J. H. Reynolds, 3 February 1818, The Major Works, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001) 377

[8] Samuel Taylor Coleridge, ‘Biographia Literaria’, XIV, in The Major Works, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008) 317 (Placeholder1)

[9] William Wordsworth, Preface to Lyrical Ballads, The Major Works, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000) 598

[10] Archibald MacLeish, Collected Poems, (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company) pp 40-41

[11] T. S. Eliot, Points of View, (London: Faber and Faber, 1945) 34

[12] Samuel Johnson, Life of Milton, (Oxford: Clarendon Press,1905) 208

[13] "Emily Dickinson." Oxford Essential Quotations. Ed. Ratcliffe, Susan. : Oxford University Press, , 2016. Oxford Reference. Date Accessed 15 Oct. 2025 <https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780191826719.001.0001/q-oro-ed4-00003636>

[14] Sir Philip Sidney, A Defense of Poesy, (Boston: Ginn & Company, 1890) 35

[15] W. H. Auden, ‘In Memory of W. B. Yeats’ in W.H. Auden: Collected Poems, (London: Faber and Faber, 1994), 248.

[16] William Carlos Williams, Introduction to The Wedge, <https://www.poetryfoundation.org/articles/69410/introduction-to-the-wedge> accessed on 15.10.25 at 17:05

[17] Don Paterson, Rhyme and Reason, <https://www.theguardian.com/books/poetry/features/0,12887,1344654,00.html> accessed 15.10.25 at 17.07

[18] Thomas Hardy, in Florence Hardy, The Life of Thomas Hardy, 1840-1928 (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1985) 417

[19] Derek Mahon, Introduction to Harry Clifton, The Desert Route, (Dublin: Gallery Press, 1992) 10

[20] William Wordsworth, ‘My heart leaps up when I behold’, The Major Works, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000) 246

[21] Pablo Picasso to Herbert Read, Oxford Essential Quotations. Ed. Ratcliffe, Susan: (Oxford University Press, 2016). Oxford Reference. Date Accessed 16 Oct. 2025, 21:03 <https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780191826719.001.0001/q-oro-ed4-00008745>.

[22] Jacques Derrida, 'Che cos'è la poesia?', from A Derrida Reader: Between the Blinds, ed. Peggy Kamuf (London and New York: Harvester Wheatsheaf, 1991), 227

[23] Samuel Johnson, in The Bloodaxe Book of Poetry Quotations, ed. Dennis O’Driscoll, (Northumberland: Bloodaxe Books, 2006) 7

[24] Samuel Johnson, in The Bloodaxe Book of Poetry Quotations, ed. Dennis O’Driscoll, (Northumberland: Bloodaxe Books, 2006) 7

[25] Derek Mahon, ‘The Forger’ in Collected Poems, (Loughcrew: Gallery Press, 2007) 24

[26] “Poem, N., Etymology.” Oxford English Dictionary, Oxford UP, September 2025, <https://doi.org/10.1093/OED/3096634241>

[27] W. B Yeats, ‘To be Carved on a Stone at Thoor Ballylee’, The Major Works, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000) 94

[28] Michael Longley, Reading the Future: Twelve Writers from Ireland in Conversation with Mike Murphy, (Dublin: Lilliput Press Ltd, 2000)

[29] T. S. Eliot, ‘Philip Massinger’, The Sacred Wood: Essays on Poetry and Criticism, (London: Methuen and Co., 1920) 114

[30] Ibid

[31] Seamus Heaney, on ‘Door into the Dark’, Don’t Ask Me What I Mean: Poets in Their Own Words, (London: Picador, 2003) 101

[32] Louis MacNeice, ‘Nature Morte’, Collected Poems, (London: Faber, 2007) 23

[33] Derek Mahon, The Poetry Nonsense: A Docudrama, Selected Prose, (Loughcrew: Gallery Press, 2012) 24

[34] Derek Mahon, ‘Poetry in Northern Ireland’, in Twentieth-Century Studies, No. 4, Nov. 1970, p.93.

Andrew Jamison is a poet and teacher, and you can read more articles on his blog here or get a paid subscription and access all previous and future posts here. You can also browse his poetry collections and buy signed, first editions of each of them here.

Comments